Reflecting on building my own tools from scratch and 'inventing on principle'

building tools inventing on principleIntroduction

For the past couple of months, I’ve built personal tools completely from scratch. I built a way to organize and record my thoughts. I built a programming language to understand Lisp. I built a tool to generate cards for family and friends. I built a web framework from scratch. I used that web framework to ship a couple of projects.

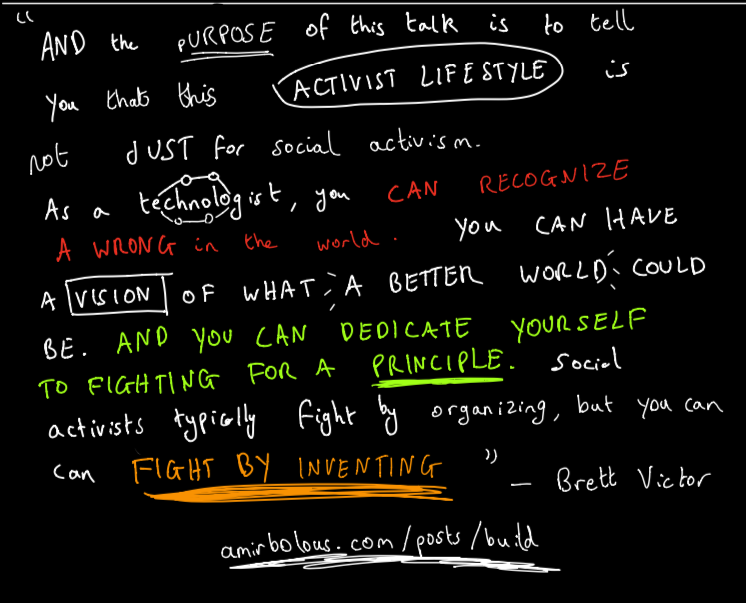

The weird thing is that, until recently, I didn’t know that I could do this. I didn’t even realize this was an option or move I could make. I didn’t know that if I had an opinion for how things should be, I had the right to push my view of the world into reality by doing something about it. Bret Victor has an incredible talk called “Inventing on Principle” where he touches on just this.

Several months later of trying to do this, I can see exactly what he meant. Here’s a story/reflection on this:

Tools and Products

Every now and then, a new tool or technology becomes mainstream and garners a passionate cult of followers advocating for it. For example, this happened with Roam. This happened with Notion. This has been happening with tools and technologies long before we invented them. Often, when I would try these mainstream tools, some of them stuck. However, more often than not, I was left confused and somewhat disappointed.

That’s not to say that these tools or technologies are not great products. Not at all. They’re clearly good products because many people use them and recommend them to others.

Dogma

I realize now that reason these products or technologies didn’t stick was because of a misaligned dogma. This is the mental model I now keep in mind: any product or tool has the potential to be great if it can solve a high frequency, high intensity problem for at least one person. Sometimes, it can even be a low frequency, high intensity problem or vice versa. For example, Uber solved the problem of moving from one place to another conveniently. React helped tackle building fast, flexible, and rich websites.

However, any technology or tool also imposes an expensive cost. It carries a dogma for how things should be. A set of implicit (e.g. react component patterns) or explicit (e.g you can’t call an Uber if no driver is nearby) rules that are imposed on how you use the tool/technology and think about it to get some value out of it. To go back to the React example, React carries a certain dogma for how you should build websites to take advantage of it. You can’t really use it if you don’t understand the pattern of “components” which is an abstraction that drives how you use the tool.

For people who have a high frequency and high intensity problem, the cost (i.e. the dogma that is “imposed” on you) feels like an absolute bargain. It can solve your pressing problem, so who cares? You’ll gladly compromise.

However for others who don’t necessarily have a high frequency, high intensity problem, these tools or products often don’t stick. This is precisely what happened with me in the past when trying out tools or technologies that had garnered any sizable number of followers but had personally not stuck. I realize now that the problem was not with the tool itself. It was with the model I personally carried that motivated my use of the tool.

When you build your own tools, products, or technologies, this is not an issue by definition. Since you’re building it yourself, the tool or technology perfectly embodies your dogma. You have a crystal clear mental model for how the tool should be used because you built it yourself! It doesn’t matter whether others get it or not. It doesn’t have to apply to a large group of people to capture a large market. It just has to work for you.

Building is Empowering

The best adjective I can use to describe building my own tools is empowering. Here’s why:

-

Because I was building the tool for myself, I had complete agency in how I chose to build it. I could tailor the tool exactly to my personal workflow and have it cater to my needs. If my needs change, no problem, I could change the tool! This is essentially a living embodiment of the Unix philosophy of “do one thing and do it well.”

-

For more low-level tools where I was building a tool that would let me use it to build other things with it (e.g Poseidon or Lispy), I had an intimate relationship with the software. Intimate in this context means I understood every aspect of the system. I didn’t necessarily remember every aspect of the system and I often forgot how I’d designed something, but this was easily fixable. I wrote the code so I could go back and look through what I wrote. This is a particularly special feeling because the software stack has become so deep that it’s become normal to compromise on our understanding of the system.

-

Because I built the tool for myself and understood the system well, it gave me the freedom to iterate quickly. I didn’t struggle setting the system or environment up. I didn’t run into obscure errors that required a nuanced understanding of a system I had just started learning. And most importantly, I had a good mental model for how I should use the system. Because I built it myself! And any tool is only as useful as the mental model you have for the system itself.

-

Because building your own tools often pushes a new layer onto the software stack, debugging was also more challenging. Bryan Cantril has a great talk on this called debugging pathological systems. The short summary is that pathological systems are hard to debug because you don’t know what level of the software stack introduced the failure. Often a failure at the low levels of the system produced several different errors higher up. The cool thing was that these types of errors force you to understand the system better. Debugging didn’t feel like I was struggling with a beast in the dark. It felt like learning a complex dance with a partner (this summarizes some of the more helpful tips). It was still frustrating, but I often came through on the other side with a much clearer picture of the nuances of the system.

-

Maybe most importantly, building everything from scratch is incredibly satisfying and rewarding. Even if it’s a little slower or it’s a little harder to push out features because there isn’t a team behind the product. Not only do the tools or technologies fit your use cases and workflows perfectly, it gives you an emotional connection to the products you use. In the same way that you appreciate an accomplishment much more once you’ve experienced something similar yourself. For example, after I ran a marathon last year, I gained a lot more respect for athletes, especially marathoners with really fast times because I’ve experienced how painful doing one is! Similarly building things for yourself gives you a sense of enjoyment and excitement that is just incomparable to when you use a product that others have built.

Closing Thoughts

As with all things, this is a process and a journey. I did not wake up overnight deciding to embrace this philosophy. And I’ve only just started. I’ve got a long way to go. There are many others who inspire me and who I learn a lot from.

So no, you don’t have to build everything for yourself from scratch. And no you should not stop using every great product out there. But know that this is an option. When there are times where you wish something existed in the world. Or you’re frustrated there isn’t a better solution. You can and have the right to create one yourself. In fact, if you feel obliged to do so, you should do it. Stand on the shoulders of giants, steal like an artist, and build what you wish existed for yourself and others to use.

If you’ve got this far, I would love to hear what you think, please say hi on Twitter.

Happy building 🚀